By Rob Lamberton, BSc, FNTP, FDN-P (Candidate)

Product Formulator & Functional Health Consultant

roblamberton.com

🌿 Rediscovering a Forgotten Element

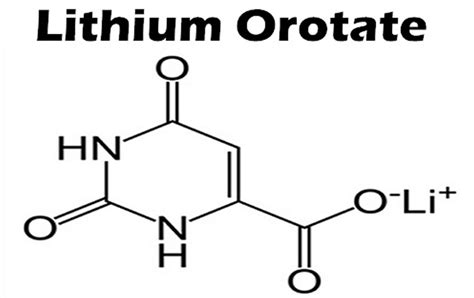

Lithium — one of Earth’s simplest elements — has an unexpectedly profound relationship with human biology. For decades, lithium carbonate (LC) has been prescribed in psychiatry as a potent mood stabilizer. But recent research has reignited interest in a far gentler form: lithium orotate (LO), a micro-dose compound now being explored for its potential neuroprotective and longevity benefits.

A 2025 Nature study from Harvard Medical School revealed a startling finding: brain lithium deficiency correlated with Alzheimer’s-like changes in both human and animal brain tissue. Even more striking, when researchers administered low-dose lithium orotate, it reversed these pathological changes, improved mitochondrial health, and restored memory function in Alzheimer’s-model mice (Aron L et al., Nature, 2025).

This study, along with several human and ecological data sets, is reframing lithium not as a psychiatric drug — but as a trace brain nutrient essential for long-term neurological integrity.

🧬 How Lithium Protects the Brain

At micro levels, lithium interacts with cellular pathways that regulate neuroplasticity, mitochondrial function, and oxidative stress. Its key actions include:

- GSK-3β modulation, reducing tau phosphorylation and amyloid plaque buildup (major Alzheimer’s mechanisms)

- Upregulation of BDNF, supporting neurogenesis and synaptic repair

- Stabilization of neuronal calcium and glutamate signaling, improving stress tolerance and mood regulation

- Reduction of neuroinflammation, preserving mitochondrial DNA integrity

A landmark 15-month human trial (Nunes MA et al., J Alzheimer’s Dis., 2013) showed that micro-dose lithium stabilized cognition in Alzheimer’s patients versus placebo. Meanwhile, global population studies (Fraiha-Pegado J et al., Nutrients, 2024) show that communities with higher trace lithium levels in drinking water have lower rates of dementia and suicide.

Together, these data suggest that trace lithium plays a subtle but essential neuroprotective role — one that may help safeguard cognitive longevity.

⚖️ Lithium Orotate vs. Lithium Carbonate: The Critical Distinction

While both compounds deliver the same elemental ion (Li⁺), their pharmacology, safety, and intended use differ dramatically.

Lithium Orotate (LO)

- Available as an over-the-counter supplement

- Typically delivers ~5 mg elemental Li⁺ per capsule

- Used at micro-doses for nutritional and neuroprotective support

- Human data indicate a low toxicity profile at these doses (Murbach TS et al., Regul Toxicol Pharmacol., 2021)

Lithium Carbonate (LC)

- Prescription medication for bipolar disorder and mood stabilization

- Provides 100–300 mg elemental Li⁺ daily

- Requires regular blood-level monitoring

- Associated with renal and thyroid toxicity during long-term use (Gong R et al., Kidney Int Rep., 2016)

Both provide lithium — but their dose magnitude and biological outcomes are profoundly different. LO functions as a nutritional cofactor, not a pharmaceutical intervention.

⚠️ Safety First

Although LO’s preclinical safety profile is strong, human data remain limited. Practitioners and consumers alike should use it with respect and professional guidance.

Avoid use:

- During pregnancy or breastfeeding

- In cases of renal impairment or thyroid disease

- Alongside diuretics, sedatives, or prescription lithium carbonate

Micro-dosing (1–5 mg elemental Li⁺ daily) appears well-tolerated, but higher doses risk crossing into pharmacologic territory.

💡 Formulator’s Insight

As a Product Formulator & Functional Health Consultant, I view lithium orotate as one of the most promising precision micronutrients in neuro-longevity science.

In properly structured formulas, LO can play a supportive role in mood, focus, and cognitive resilience formulations — especially when synergized with:

- Adaptogens like Rhodiola rosea and Ashwagandha for HPA-axis balance

- Nootropics like Bacopa monnieri, L-Theanine, and phosphatidylserine for focus and clarity

- Mitochondrial nutrients such as CoQ10, Acetyl-L-Carnitine, and PQQ for energy and neuroprotection

In these combinations, LO acts not as a drug but as a trace element catalyst — gently supporting synaptic signaling, mood stability, and mitochondrial repair.

The next evolution in formulation science will integrate compounds like LO within multi-pathway brain health systems that combine adaptogenic, mitochondrial, and genomic support.

🧩 The Future of “Neuro-Longevity”

Lithium orotate represents a bridge between psychiatry and functional medicine — a small molecule with outsized potential for neural preservation and emotional balance.

It may soon join other “longevity micronutrients” such as ergothioneine, nicotinamide riboside, and sulforaphane as part of a new generation of evidence-based, neuroprotective formulations that focus on healthspan rather than disease treatment.

📚 Key References

- Aron L, et al. Nature, 2025 — “Brain Lithium Deficiency and Alzheimer’s Pathology.”

- Nunes MA, et al. J Alzheimer’s Dis., 2013 — “Microdose Lithium Stabilizes Cognitive Decline.”

- Fraiha-Pegado J, et al. Nutrients, 2024 — “Trace Lithium in Water and Dementia Risk.”

- Murbach TS, et al. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol., 2021 — “Toxicological Evaluation of Lithium Orotate.”

- Gong R, et al. Kidney Int Rep., 2016 — “Lithium and the Kidney.”

- Kory P, Substack – The Forgotten Elements, 2025 — “Micro-Lithium and Brain Aging.”

🤝 Work With Me

I collaborate with nutraceutical companies, functional clinics, and longevity brands to develop evidence-based product formulations for cognitive, mood, and mitochondrial health.

If your organization is creating the next generation of nootropic, adaptogenic, or brain-longevity products, let’s connect.

🌐 roblamberton.com

🌿 Rediscovering a Forgotten Element

Lithium — one of Earth’s simplest elements — has an unexpectedly profound relationship with human biology. For decades, lithium carbonate (LC) has been prescribed in psychiatry as a potent mood stabilizer. But recent research has reignited interest in a far gentler form: lithium orotate (LO), a micro-dose compound now being explored for its potential neuroprotective and longevity benefits.

A 2025 Nature study from Harvard Medical School revealed a startling finding: brain lithium deficiency correlated with Alzheimer’s-like changes in both human and animal brain tissue. Even more striking, when researchers administered low-dose lithium orotate, it reversed these pathological changes, improved mitochondrial health, and restored memory function in Alzheimer’s-model mice (Aron L et al., Nature, 2025).

This study, along with several human and ecological data sets, is reframing lithium not as a psychiatric drug — but as a trace brain nutrient essential for long-term neurological integrity.

🧬 How Lithium Protects the Brain

At micro levels, lithium interacts with cellular pathways that regulate neuroplasticity, mitochondrial function, and oxidative stress. Its key actions include:

- GSK-3β modulation, reducing tau phosphorylation and amyloid plaque buildup (major Alzheimer’s mechanisms)

- Upregulation of BDNF, supporting neurogenesis and synaptic repair

- Stabilization of neuronal calcium and glutamate signaling, improving stress tolerance and mood regulation

- Reduction of neuroinflammation, preserving mitochondrial DNA integrity

A landmark 15-month human trial (Nunes MA et al., J Alzheimer’s Dis., 2013) showed that micro-dose lithium stabilized cognition in Alzheimer’s patients versus placebo. Meanwhile, global population studies (Fraiha-Pegado J et al., Nutrients, 2024) show that communities with higher trace lithium levels in drinking water have lower rates of dementia and suicide.

Together, these data suggest that trace lithium plays a subtle but essential neuroprotective role — one that may help safeguard cognitive longevity.

⚖️ Lithium Orotate vs. Lithium Carbonate: The Critical Distinction

While both compounds deliver the same elemental ion (Li⁺), their pharmacology, safety, and intended use differ dramatically.

Lithium Orotate (LO)

- Available as an over-the-counter supplement

- Typically delivers ~5 mg elemental Li⁺ per capsule

- Used at micro-doses for nutritional and neuroprotective support

- Human data indicate a low toxicity profile at these doses (Murbach TS et al., Regul Toxicol Pharmacol., 2021)

Lithium Carbonate (LC)

- Prescription medication for bipolar disorder and mood stabilization

- Provides 100–300 mg elemental Li⁺ daily

- Requires regular blood-level monitoring

- Associated with renal and thyroid toxicity during long-term use (Gong R et al., Kidney Int Rep., 2016)

Both provide lithium — but their dose magnitude and biological outcomes are profoundly different. LO functions as a nutritional cofactor, not a pharmaceutical intervention.

Of Note: Here in Canada, Health Canada does not distinguish between Lithium Orotate and Lithium Carbonate – they consider both to be restricted prescription drugs!

⚠️ Safety First

Although LO’s preclinical safety profile is strong, human data remain limited. Practitioners and consumers alike should use it with respect and professional guidance.

Avoid use:

- During pregnancy or breastfeeding

- In cases of renal impairment or thyroid disease

- Alongside diuretics, sedatives, or prescription lithium carbonate

Micro-dosing (1–5 mg elemental Li⁺ daily) appears well-tolerated, but higher doses risk crossing into pharmacologic territory.

💡 Formulator’s Insight

As a Product Formulator & Functional Health Consultant, I view lithium orotate as one of the most promising precision micronutrients in neuro-longevity science.

In properly structured formulas, LO can play a supportive role in mood, focus, and cognitive resilience formulations — especially when synergized with:

- Adaptogens like Rhodiola rosea and Ashwagandha for HPA-axis balance

- Nootropics like Bacopa monnieri, L-Theanine, and phosphatidylserine for focus and clarity

- Mitochondrial nutrients such as CoQ10, Acetyl-L-Carnitine, and PQQ for energy and neuroprotection

In these combinations, LO acts not as a drug but as a trace element catalyst — gently supporting synaptic signaling, mood stability, and mitochondrial repair.

The next evolution in formulation science will integrate compounds like LO within multi-pathway brain health systems that combine adaptogenic, mitochondrial, and genomic support.

🧩 The Future of “Neuro-Longevity”

Lithium orotate represents a bridge between psychiatry and functional medicine — a small molecule with outsized potential for neural preservation and emotional balance.

It may soon join other “longevity micronutrients” such as ergothioneine, nicotinamide riboside, and sulforaphane as part of a new generation of evidence-based, neuroprotective formulations that focus on healthspan rather than disease treatment.

📚 Key References

- Aron L, et al. Nature, 2025 — “Brain Lithium Deficiency and Alzheimer’s Pathology.”

- Nunes MA, et al. J Alzheimer’s Dis., 2013 — “Microdose Lithium Stabilizes Cognitive Decline.”

- Fraiha-Pegado J, et al. Nutrients, 2024 — “Trace Lithium in Water and Dementia Risk.”

- Murbach TS, et al. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol., 2021 — “Toxicological Evaluation of Lithium Orotate.”

- Gong R, et al. Kidney Int Rep., 2016 — “Lithium and the Kidney.”

- Kory P, Substack – The Forgotten Elements, 2025 — “Micro-Lithium and Brain Aging.”

🤝 Work With Me

I collaborate with nutraceutical companies, functional clinics, and longevity brands to develop evidence-based product formulations for cognitive, mood, and mitochondrial health.

If your organization is creating the next generation of nootropic, adaptogenic, or brain-longevity products, let’s connect.

🌐 roblamberton.com